Undergrad Capstone

I am including my undergraduate capstone in this because it represents quite a bit of research and was the reason I became so focused on obtaining a Ph.D. in Cultural diplomacy with a focus on food studies.

Food Writing in Literature: Why it Matters

Gina C. Ruiz

Northeastern University

Author Note

This paper is submitted as the capstone project in Liberal Studies.

Table of Contents

Food Writing in Literature: Why it Matters. 5

Why Food Writing in Literature Matters. 10

Food Writing in Ancient Writings. 10

Food Writing and What it Does. 13

Food Writing’s Ubiquity in Literary Texts. 14

Food Writing and Semiotics. 15

Food Writing Transcends Genre and Overflows to Others. 17

Food Writing and the Literary Cookbook. 26

Food Writing in Culinary Memoir/Gastrography. 27

Food Writing, the Literary Table, and Culture. 32

Food Writing and What It Hides. 41

Food Writing and the Accidental Historian. 42

Food Writing and Philosophy. 44

This paper explores food writing in literature and how it transcends genre, is integral to writing, and acts as a signifier for cultural, anthropological, sociological, historical, and issues. Further, this paper discusses how food writing can sometimes hide meaning, act as its own literary device while using those same devices as tools to engage the reader and to explore the self. Food is everywhere in literature, it is a signifier, and it is fundamental to writing.

Keywords: alimentary history, alimentary writing, ancient literature, books, class, classics, chefs, cooking, cookbooks, culinary history, culinary metaphorics, culinary psychopolitics, writing, era, food, food culture, food history, food philosophy, foodways, food writing, food writing in history, gastrography, gastronomic sociology, genre, gustatory narrative, identity, literary meals, literary signifiers, literary device, literary text, literature, metaphorics, place, poets, poetry, power, recipes, sapience, selfhood, semiotics, setting, signposts, socioeconomic status, symbolism, time, writers.

Food Writing in Literature: Why it Matters

Food is everywhere in literature, it is a signifier, and it is fundamental to writing. Food writing has existed since humans began writing. In actuality, the act of using food as a literary signifier was in existence before writing via oral, storytelling tradition. Because food is vital to human existence, the act of using food as a literary or storytelling device pre-dates writing, though it exists through our written words as a living, evolving, and complex history of humankind. Food writing in literature illustrates how humans have lived, what they ate, how they ate it, where they procured food, and what types of food people went to war over. It also aids in illustrating how humans arrange themselves into societies as well as how we exclude others. Food writing in literature can help the reader understand other cultures and historical periods by showcasing or highlighting those cultures, eras, foodways, and knowledge. It can reflect diets, mannerisms, customs, hungers and desires, needs, and tastes. Food writing is everywhere in literature, it acts as a signifier and is fundamental to writing.

Because food writing is vital to literature as a whole, it transcends genre, wrapping its long, curvaceous tentacles around nonfiction, science fiction, fiction, fantasy, children’s literature, crime fiction, political writing, cookbooks, culinary memoirs, memoirs, biographies, poetry, comics and graphic novels, journals and diaries, letters, travelogues, plays, and textbooks. Food writing is ubiquitous in literature and uses various literary devices such as simile, metaphor, allusion, symbolism, motifs, imagery, etc., but is also, in and of itself, a literary device. Food writing in literature is critical because food to humans is necessary. The way food is documented in literature can act as a literary signifier or cultural signpost, help illustrate and flesh out a character, or show the reader a history of a people, time, or place.

Food as a literary device can act as signpost, leading the reader on a path to understanding a culture, a character, an era, a place, story, religion, theme, or motif. Food can speak to a reader of politics, memory, socioeconomic status, war and peace, hunger, and desire. It can highlight racism or transphobia, bigotry, unfairness, and cruelty. The food writing in literature can tell us about the seasons and the labor it takes to get food to the table. Food writing can be memory-of historical events, childhood, etc.. Food writing in literature matters because it is profoundly and powerfully connected to the mechanics of literary author-reader engagement. It can function as a political litmus test of an era and zeitgeist, enable cross-cultural dialogue, can promote conflict, inspire creativity, and mushroom into other genres or mediums, all the while deepening a reader’s understanding of the literary text. Food is everywhere in literature, it is a signifier, and it is fundamental to writing.

Literature Review

Food writing matters in literature. This is substantiated by the history of food writing and how it transcends genre, helps the reader connect with literary text and understand different worlds, its functions as a signifier, affects and is affected by culture. Food writing in literature closely aligns with identity and selfhood of the author and/or reader.

Denise Gigante has written many articles in the field of Romanticism and Taste. Her book Taste: A Literary History (Gigante, Taste: A Literary History, 2005) provides an excellent insight into how the Romantics helped to shape the gustatory narrative and illuminates how such icons as Byron, Keats, and Milton used the gustatory narrative in their writing. Gigante also edited the volume Gusto: Essential Writings in Nineteenth-Century Gastronomy, which provided an essential overview into the history of gastronomy as well as its impact on the literature of the era.

Food has functioned in literature of all types for millennia, but as an academic field, the formal study of food in literature dates only to the 2010s. A prominent, early authoritative source is “Food and Literature: An Overview” chapter by Joan Fitzpatrick (the leading expert in the field of Shakespeare and Food) in the Routledge International Handbook of Food Studies. (Fitzpatrick, 2012). In this chapter, Fitzpatrick discusses how important developments in the field of food and addresses the large gaps in this emerging field of study. Fitzpatrick examines the need for monographs on food-related writings of Ben Johnson, Dickens, poetry and prose, Milton, and Spencer, amongst others. She notes that while there has been some study in prose and poetry, much more is needed. Her work highlights potential avenues of research and gives an excellent overview into food studies as they pertain to literature, as well as the history of studies in this field.

Allison Carruth, in 2013, published a monograph entitled Global Appetites: American Power and the Literature of Food (Carruth, 2013). Carruth studies how food writing in American literature has both affected and reflected institutions of power – such as capitalism, the modern food system, and even world hunger – in the United States and worldwide. The book also explores industrial agriculture, counter-culture movements and how they shape ideas of U.S. hegemony. Carruth argues that American food power is central to the history of globalization and examines what effects it has on regional cultures and ecosytems.

In 2018, Routledge published The Routledge Companion to Literature and Food, edited by Lorna Piatti-Farnell and Donna Lee Brian. This is the first, comprehensive compilation of food studies as it exists within the field of literature. It states, “’Literary food studies’ can be viewed as a new and emerging field of inquiry, which re-evaluates, re-thinks, and rediscovers, the importance of food and eating in understanding the ways we live and communicate” (Piatti-Farnel & Brien, 2018). This extensive volume includes forty-three chapters on various ways food in literature is impactful, from graphic novels, to cookbooks, to memory, and even the food blog as ‘culinary autobiography.’ The editors mention how much scholarly attention and works fall within the broad scope of “food and literature” and the many disciplines it encompasses.

Literature and Food Studies, also published in 2018 by Routledge (Tigner & Allison, Literature and Food Studies, 2018), gives an overview of the discipline, calling it a “growing, interdisciplinary field.” This volume provides historical insight and the expansive scope within the field of literature and food studies.

In 2020, Cambridge University published their first Companion to Food and Literature, edited by Michelle Coughlan, who states that, “literature…offers unique insight into the complexity of food matters even as it works at once to archive and refashion our tastes in a gastronomic sense” (Coughlan, 2020). This collection of sixteen essays on food provide an overview of representations of food in literature from various standpoints, such as alimentary activism, gender and sexuality, critical race studies, eco criticism, cookbooks, etc.

Most recently, in November, 2020, a volume entitled, Consumption and the Literary Cookbook, edited by Roxanne Harde and Janet Wesslius, (Harde & Wesselius, 2020), that examines literary cookbooks and the narratives therein. It is the first academic volume solely focusing on cookbooks and discusses extensively why and how literary cookbooks are written.

Cultural reference works in the humanities and social sciences collectively provide insight into how food fits into the culture, ethnography, social status, and thoughts of humankind. These include M.F.K. Fisher’s translation of Brillat-Savarin’s The Physiology of Taste (Brillat-Savarin, 1986), volumes by Margaret Visser ( (Visser, Much Depends on Dinner, 1986) (Visser, The Rituals of Dinner, 1991), Tasting Food, Tasting Freedom (Mintz, 1996), The Taste Culture Reader (Korsmeyer, 2005), The Oxford Companion to Food (Davidson, 2006), Massimo Montanari (Montanari, Food is Culture, 2006) (Montanari, Let the Meatballs Rest and Other Stories About Food and Culture, 2012), Bruno Bettelheim’s The Uses of Enchantment (Bettelheim, 2010), Foodies (Johnston & Baumann, 2010), Food and Culture: A Reader (Counihan & Van Esterik, 2013), Nicola Perullo’s Taste as Experience, (Perullo, 2016), Chris Ying’s you and I Eat the Same (Ying, 2018), Alexandra Plakias’ Thinking Through Food (Plakias, 2019).

A number of historical monographs from the late 20th and early 21st century demonstrate persuasively that food has been an integral part of literature since its beginnings and in fact, prior to the invention of writing. This history is illuminated in Food in History (Tannahill, 1973), Food: A Culinary History (Flandrin & Montanari, 1999), Felipe Fernández-Armesto’s work (Fernádez-Armesto, 2004) (Fernández-Armesto, 2002), Cuisine and Culture (Civitello, 2004), Savoring Power, Consuming the Times (Palma, 2013), An Edible History of Humanity (Standage, 2009), The Rise and Fall of Adam and Eve (Greenblatt, 2017), and The Written World (Puchner, 2017).

As noted above, there is not only a significant contributory body of work on the emerging discipline of literary food studies but also numerous adjunct contributions from other fields. The field of study is so vast, and touches on so many genres and disciplines, that there remains significant room for study, such as in the areas of food in Dickens, Latinx literature, French literature in English, food in historical fiction novels, and food in science fiction and fantasy literature, and more. Food writing as a literary device remains unexplored except in adjunct to other disciplines and should be examined on its own.

Why Food Writing in Literature Matters

Food writing in literature spans multiple genres and disciplines. It has existed for millennia and has been a potent literary device. Food writing in literature is a vast field with much room for study. The following sections outline, some of the ways food writing influences literature and why that influence matters.

Food Writing’s History

Food, like many other subjects, has been a topic of human language and art since the days of cave paintings and oral storytelling. The first known instance of a written literature is the First Tales of Gilgamish (Puchner, 2017) before 2100 B. C., (as noted in David Lindroth’s map of the Written World in Figure 1), in present day Iraq. However, the first written recipes, written in cuneiform on this tablets that survived in the Akkadian language. These tablets record recipes from Mesopotamia about 1600 B.C. (Abala, 2014). This primary source illustrates that cooking and food were vital, so much so, that recipes were written down. In the First Tales of Gilgamesh, Gilgamesh himself becomes a writer, “He brought back tidings from before the flood/From a distant journey came home, weary, at peace/Engraved all his hardships on a monument of stone” (Puchner, 2017, p. 33). Since those first cuneiform letters were pressed into clay, humans have used writing as a means of conveying information and telling stories. As storytelling evolved into written language, so too did the incorporation of food.

Food Writing in Ancient Writings

In our earliest known writings, there is writing about food. For example, in The Epic of Gilgamesh, Enkidu is a wild thing, eating grass like beasts in the field. He is offered bread and beer but does not know how to eat or drink it. Once he does, however, he sheds his savage mien and acquires humanity and civilization: “His body with oil he anointed. He became like a man. He attired himself with clothes even as does a husband” (Langdon, 2006). Enkidu becomes a man by the process of eating prepared food. It imbues him with humanity. As such, food is a metaphor for humanity. It exists in this ancient Sumerian text as a literary device and cultural signifier.

Another example of food bestowing humanity on the eater is found in the Bible. Eve eats the fruit of the tree of knowledge and shares it with Adam. “They then know shame for their nakedness” (Carroll, 1997, 3 Gen. 7:10). Adam and Eve are exiled from Paradise because of her crime/sin of eating from the Tree of Knowledge. The two lose their innocence, are deprived of Paradise, and gain humanity. In the Bible, the fruit of the tree is used as a literary device. What is interesting about the two texts is that in Gilgamesh, Enkidu’s humanity is seen as something to strive for – a gift. The harlot who supplies bread and beer and teaches Enkidu how to eat them is viewed in a different light than Eve. The harlot bestows knowledge and humanity through food (and sex) and she is not viewed unfavorably. In the Bible, Adam and Eve’s humanity is punishment for their transgression of eating the apple (and clothing themselves) (Carroll, 1997, 3 Gen. 16). In this instance, the fruit of the tree, is a metaphorical food that bestows not only humanity upon Adam and Eve, but also guilt, shame, loss, pain, and exile. Further, Eve is maligned for partaking of the fruit, and the biblical God gives Adam dominion over her, even though he, too, ate the apple. [1]

In both ancient texts, food plays an integral role not just in the plot, but in the underlying theme of the story. Each narrative uses metaphor and symbols as literary devices to explore its own view of human existence. The two texts represent two different cultural perspectives and historical eras. The concept of humanity itself varies between the texts: in Gilgamesh, food bestows the “gift” of humanity; in the Bible, humanity is a punishment for eating from the Tree of Life. Food leads to humanity in each instance, but the narratives clearly demonstrate that these two ancient cultures viewed ‘being human’ in fundamentally different ways.

John Milton also wrote about biblical food in Paradise Lost and Regained. Denise Gigante, examines Milton’s food aesthetics in a journal article in 2000 (Gigante, Milton’s Aesthetics of Eating, 2000). In this piece, Gigante reflects on Milton’s gustatory aesthetics and how taste plays a part in both Paradise Lost and Paradise Regained. In these works, Milton describes the biblical meal from the Tree of Knowledge. Gigantes explains that in Milton’s version of this meal, the word “eat” dangles. “Visually, it dangles from the end of each line like the forbidden fruit itself, suggesting something sinful about eating, as if paradise were lost because despite whatever else they were doing, Adam and Eve ate” (Gigante, Milton’s Aesthetics of Eating, 2000, p. 90). Gigante’s interpretation of Milton echoes that Adam and Eve’s humanity was punishment for eating the forbidden fruit.

Using food as a symbol and motif in literature existed in early human’s oral storytelling, cave paintings, and myths. Food, as a literary device, was used to explain and instruct. Why? Because food is essential to human life. It sustains life. Without food, we starve. The quality of the food and diet we eat can change how we live, how healthy or unhealthy we are, and how long we live. Ancient peoples were driven to learn agriculture, teamwork, hunting techniques, weapon-making, etc., to survive and thrive. It makes sense that food would become an important and easily understandable literary device to educate or entertain in our earliest storytelling traditions. When humans began to have written languages and stories, naturally, they incorporated that age-old literary device of using food to instruct and make sense of the world around them in the new form of written communication.

Homeric epics and myths, which were sung, also used food to convey meaning. Such is that of Demeter’s myth, which is centered on seasons, harvest, motherhood, and one fruit – the pomegranate. In that myth, Persephone, the daughter of Demeter, is kidnapped by Hades and taken to the underworld. Demeter, stricken with grief, stops growing things and the world is plunged into famine. While in the underworld, Persephone is forcibly given “a honey-sweet pomegranate seed to eat” (Raynor, 2014, p. 29) and so is doomed to spend one-third of the year underground as Hades’ queen. When Persephone returns to her mother above ground in the Spring, everything flourishes. It is only after Zeus orders Demeter to grow food for humankind, that she again acts out her duties as a harvest deity (Raynor, 2014, pp. 17-34). In this way, Homer’s use of food as metaphor explains famine, trickery, grief, motherly love, and coercion, but also glorifies and obfuscates rape. Persephone’s words to her mother, that…”secretly Kronos’ other son put into me a pomegranate seed, honey-sweet food, compelling me by force to eat, most unwillingly” (Raynor, 2014, p. 31). all allude to rape. The Ancient Greeks were using the literary devices of allusion, symbolism, and food to sing their myths in order to try to explain what their world and culture was like, how the seasons worked, and how dangerous it was for young women to be out alone.

Food Writing and What it Does

Food writing in literature gives a sense of place, time, politics, socioeconomic status, and culture. It is ubiquitous in literature because it is such an important means of signaling a historical period, setting, culture, disparate socio-economic statuses, politics, etc. The semiotics of food as they appear in culinary writing within literary texts illustrate various aspects of human life and what we, as humans, care about. Such writing acts as a cultural or historical signpost as well as literary device. Food writing in literature enables us to situate the narrative in a spatiotemporal cultural environment. Food writing can also obfuscate certain problematic issues such as imperialism, racism, colonization, bias, etc. by focusing on the enjoyment or ingredients of a meal without delineating how, why, or from where from that meal or food product came to the table or historical era. Even in historical writings or other nonfiction, a food or meal can hide meaning, politics, labor, etc.

Food Writing’s Ubiquity in Literary Texts

Food writing is not just a narrative technique found in cookbooks, restaurant reviews, culinary memoirs, or gastronomical magazines, nor is it a literary device used primarily by women. Rather, food writing is found across across the globe, in every type of literary text by writers of all kinds in every era that has had a written literature. The use of food at a literary device transcends genre and country, assists in creating an emotional connection with the reader, and helps increase understanding. Every person on the planet has, at one time or another, been hungry or craved a particular food. The biological need for food is universal.

Good food writing draws the reader into a setting, helps them know a character and whether that place or character are likeable. When we read about a literary meal or feast, we, the readers, form a connection that is both physical and emotional. We draw clues from that writing that informs our senses. We imagine the look of it, the smell, the taste. We are invested in that food whether it repels or seduces us. As Rachel Franks remarks, “writers use food to communicate the everyday and to explore a vast range of ideas from cultural background to social standing, and also use food to provide perspectives “into the cultural and historical uniqueness of a given social group” (Franks, 2013). Franks goes on to discuss the various ways that writers use food in their work to convey different effects, including how food is so integral to storytelling, that when it is ignored, it “is an obvious omission” (Franks, 2013). These literary omissions also can act as a type of semiotics, which make the reader think of what is absent, why it is not there, and draw conclusions based on what the writer wants to convey its absence.

Food Writing and Semiotics

In fact, food writing often acts as literary subtext of hidden, implied, and unspoken cultural, symbolic, and metaphorical language to aid in propelling the plot. In “The Semiotics of Food,” Simona Stanos references Claude Levi-Strauss’ “The Culinary Triangle,” and his philosophy that cooked food is a cultural object (Stanos, 2015, p. 650). If cooked food is a cultural object, then cooked meals in literature are as well, and carry their own semiotics or signposts indicating culture, education, class, ethnicity, location, etc.

Stanos also quotes Roland Barthes, “It [food] is also, and at the same time, a system of communication, a body of images, a protocol of usages, situations, and behavior.” (Stanos, 2015, p. 647). Barthes’ observation affirms that food acts as a type of semiotics in literature, in other words, a writer’s description of a particular food, meal, or food experience implies that the writer knows what meaning they are trying to convey. Barthes also attempted to categorize food into a sort of grammar, for example, “ordinary bread (signifying day-to-day life).” (Stanos, 2015, p. 653). Stanos, citing Montanari and others, claims that food is also a constantly evolving language (Stanos, 2015, p. 655).

This language of food is illustrated in how authors and poets write about food in their poems and stories to convey meaning and communicate cultural distinctions, social issues, politics, poverty, etc. If food is a language, as Stanos argues, then writers, in using food in their work, incorporate its meaning, symbols, and signifiers into their stories or poetry as a kind of subtext. Stanos also affirms that food transcends genre and medium, providing endless means of discourse, and asks, “What are the traces left by such discourses? And how do these traces affect our perception of reality?” (Stanos, 2015, p. 660). How indeed? The possibilities are limitless. Food writing has existed for millennia and it colors how people think, feel, connect, and live through literature. Thus, it is impossible to answer Stanos’ question with one response. In just one book, the traces left by the discourse regarding food can obfuscate certain issues, highlight others, show us how a culture lives, or deceive us into thinking that is how they live. Further, it is not just the writing and semiotics within that food literature that influence the realities we take from reading it. It is the reader themselves.

For instance, someone in the United States may read a description of a meal in the 19th-century novel Little House on the Prairie and long for the adventuresome spirit of the American frontier and its simple, home cuisine. Conversely, a Native American may read the same narrative and think about cultural appropriation, Manifest Destiny, stolen lands, or generations of suffering. Because of what each reader brings to the text, the two perceptions will be different though the food writing is static within that page or pages of that book. Similarly, a Mexican may read about tacos and guacamole in an American novel and think, ‘Well, they do not want us crossing their borders and yet, our food they celebrate and appropriate in their literature.’ While another reader interprets the meal simply as a realistic nod to everyday life in the southwestern United States. Reading is subjective, individual, and sometimes, deeply personal, therefore how we interpret the semiotics of food in literature will be different on an individual basis, though there are some elements we all share.

In fact, these differences in how we read food writing also lend themselves to translation of literature.

In “The translation of food in literature: A culinary journey through time and genres,” Anthi Wiedenmayer explains the difficulty in translating food writing in literature, i.e. “interlingual transfer of food in translations of different literature genres based on a selection of examples since the eighteenth century.” (Wiedenmayer, 2016). Widenmayer goes on to discuss Alice in Wonderland and how in German translations tea has been changed to coffee. In Sweden, another translation of Alice switches out “ginger beer” for “cranberry drink.” (Wiedenmayer, 2016, p. 36). These types of translation changes can distort an author’s original intended meaning by changing the original symbol to one that means something completely different (or, as is often the case, has no meaning at all). Although translators work diligently to provide substitutes that readers can identify and understand, inadequate translations inevitably appear and new symbols/semiotics will completely change the original gustatory narrative.

Food Writing Transcends Genre and Overflows to Others

Food writing can also inspire creativity, imagination, and produce more writing in other genres and platforms and vice versa. Consider Anthony Bourdain’s career that stemmed from his culinary memoir, Kitchen Confidential, or Diana Gabaldon’s popular Outlander novels which led to both cookbooks, books on 18th century fashion, and a popular Starz television series. Julia Child and Simone Beck’s seminal Mastering the Art of French Cooking led to fame for Ms. Child. Her cookbooks, television show, and autobiographical book, My Life in France, inspired writer Julia Powell to create a blog dedicated solely to cooking Child’s recipes over the course of a year. This blog in turn, became wildly popular and led to the film starring Meryl Streep, entitled Julie/Julia. These crossovers from literature into film, television, cookbooks, and nonfiction historical writings illustrate that good food writing can inspire and expand into other media and genres.

Another surprising genre where food writing can be found is in detective novels/crime fiction. In those novels, food is often used as a method for murder, but also to depict setting and illuminate character. Dining Room Detectives: analysing food in the novels of Agatha Christie (Buačeková, 2015), a monograph by Silvia Baučeková, examines the importance of food in the body of work of crime writer, Agatha Christie. She notes that Hercule Poirot, one of Christie’s most famous protagonists, is often seen sipping hot chocolate (Buačeková, 2015, p. 2) and discusses how references to meals and drinks contribute to the effect within the novels. Buačeková argues that “depictions of food are used to influence or construct characters, plots, or settings, and serve as literary devices; it also intends to examine how the author uses them to tackle issues of identity, crime, or memory. Baučeková concludes that food is not merely a consequence but plays a more crucial role in these novels. As illustrated by this monograph, food writing is not limited to any one genre, nor is food written in haphazardly by authors. Food, as written, often has a serious, and sometimes deadly intent. Food is not all serious though. It can illustrate humor and beauty as well. Food’s beauty is often used by poets to illustrate their preoccupation or appreciation for a certain type of food or they often use it to symbolize something else. Food is just as prevalent in poetry as it is in other genres of literature.

Food Writing in Poetry

In every type of literary genre, by every type of writer, author, or poet, there is writing about food. Food appears in poetry, such as Seamus Heaney’s “Oysters” (Heaney, 2015, p. 210):

Our shells clacked on the plates.

My tongue was a filling estuary,

My palate hung with starlight:

As I tasted the salty Pleiades.

In the poem, Heaney uses allusion as a literary device to describe the oysters, their taste, and his emotions, while at the same time, realizing that the eating of them is a privilege that is provided by labor of others (Heaney, 2015, p. 211):

The Romans hauled their oysters south to Rome

I saw damp panniers disgorge

The frond-lipped, brine-stung

Glut of privilege.”

Heaney’s writing acknowledges the labor that it took to harvest the oysters he is enjoying by writing about the history of ancient Romans hauling them to shore. By showcasing the contrast between luxury and labor, Heaney illustrates the privilege involved in eating them. We infer from the poem that not only does Heaney love oysters, he appreciates the history of them, the work involved in getting them to his plate, and the privilege he feels in enjoying them with friends. In this case, Heaney celebrates food by using a variety of poetic and literary devices to make his food writing memorable.

In his “Ode to an Onion” Pablo Neruda does much the same, extolling the virtues of a humble onion in 41 lines of free verse of uneven stanzas. Neruda compares the onion to a “Luminous flask” and compares its leaves to swords, using the literary devices of allusion and symbolism. He extols the onion and highlights its importance in the diets of poor people (Neruda, 2017, pp. 479-481). Poets, like Heaney and Neruda often use food in a metaphorical or personified way, or to symbolize other meanings.

Similarly, William Carlos Williams, in his poem, ‘This is Just to Say’ highlights a bowl of plums. “I have eaten/the plums/that were in the icebox/and which/you were probably saving/for breakfast/Forgive me/they were delicious/so sweet/and so cold.’ (Williams, 1938). In this poem, Williams writes an apology for eating the plums, but conveys so much more. The reader gets a sense of the time because of the language he chose, for example, the word “icebox” and his description of the plums gives the reader a sense of the plum’s taste and texture. We can almost feel that icy coldness and the sharp taste of the plums. Though the poem is short, it conveys quite a bit. Though plums are only mentioned once, in the second stanza, the reader can almost taste them. It is a powerful piece of food writing.

Each of the aforementioned poets uses food in some way as a literary device, to convey meaning, appreciation, apology, or a historical sense. However, even when not used as a literary device – such as the simple mention of a bowl of plums, the very semiotics that food brings to literature illustrate that food writing is its own literary device.

Food Writing as Setting

Food writing is found in more than poetry and is not the province of just one country. In Emile Zola’s classic French novel, The Belly of Paris, is set in Paris, in and around Les Halles, the famous Parisienne marketplace. As part of the 20-volume Rougon-Macquart saga, the novel gives a rich historic overview of Paris during the Second Empire. Zola uses food writing to depict the class struggle, provide setting and atmosphere, and develop characters. The novel’s protagonist, Florent Quenu, returns to his home in Paris after escaping from the dreaded prison at Devil’s Island, hoping for refuge. However, he finds the city, the people, and the politics have all greatly changed. The novel includes incredible descriptions of food in the marketplace and acts as a mis en scene for the era and location. Zola uses a wealth of literary devices, including personification, onomatopoeia, allusion, metaphor, simile, and symbolism, to infuse the food with character. For example, from Chapter 5 (Zola, 2009, p. 238) does act as a character:

The Roqueforts, under their glass bells, had a regal bearing, their fat, marbled faces veined in blue and yellow as though they were the victims of some disgraceful disease that strikes wealthy people who eat too many truffles.

In this passage, the Roqueforts are depicted as ‘fat, marbled’ and ‘veined’ liked cattle, and diseased as an imagined consequence of their consumption of costly and luxurious truffles, which less privileged people could never afford to taste. In this one sentence, Zola creates setting, character, and tone. Further, the quote demonstrates that using food writing in literature as its own literary device, can transcend genre or country, since criticism of the Roqueforts would be readily apparent even to those outside this era of French history. Finally, this vivid correlation between the bloated wealthy and food of great privilege creates an emotional connection with the reader and makes them feel they are part of the literary environment.

Food Writing and Character

In Bridget Jones’ Diary, an epistolary novel, the main character, Bridget, is often silly, drinks too much, smokes too much, and talks too much. The reader knows Bridget is rather scattered and inept, but nothing displays it more than when she decides to cook herself and guests a lovely birthday dinner (Fielding, 1996, pp. 235-236). In the ensuring hilarity, the reader knows how Bridget feels, and we know that in spite of the disastrous meal, Bridget is loved and treasured:

8:30 p.m. All going marvelously. Guests are all in living room. Mark Darcy is being v. nice and brought champagne and a box of Belgian chocolates. Have not done main course yet apart from fondant potatoes but sure will be v. quick. Anyway, soup is first.

8:35 p.m. Oh my God. Just took lid off casserole to remove carcasses. Soup is bright blue.

Bridget’s guests gamely finish the meal, her love interest helps her salvage her culinary disaster, and all is well, or at least, until the next Bridget-stye failure.

The literary devices Fielding uses in Bridget’s diary give an odd sense of time and place as well. Bridget writes as if she is in the moment. She is just now discovering the soup is blue. However, as anyone who memorializes anything in a diary knows, one does not write in the diary as events are happening, but rather, afterwards in reflection. The happening-right-this-instant writing style is a literary device that works particularly well with the instance of the blue soup. The reader feels stunned horror just as Bridget realizes her soup is blue. We are there in the kitchen, lifting that lid and discovering disaster. Fielding makes the soup blue – an unlikely color among natural foods – and this adds to the sense of comedy, rather than tragedy. We also know, via Bridget’s inner monologue/diary, that more hilarity will ensure, and no matter the disaster, Bridget will triumph in the end. We feel connected to her because, after all, who has ot experienced some sort of cooking mishap?

Interestingly, however, food plays a darker role in this novel. Do we love Bridget because she is the helpless maiden in distress? Are we allowing expected gender roles to dominate in our literature? What does it say about us as a society that we love Bridget because she is helpless, floundering, and cannot follow the directions in a recipe? We love Mark Darcy (and so does Bridget) because he comes in, rolls up his sleeves and saves dinner. The novel perpetuates the “knight in shining armor” myth from fairy tales into the modern genre of women’s fiction. How does this serve us as a society?

While Bridget Jones’ Diary is pure epistolary entertainment, light fare in the form of “chick lit,” now known as women’s fiction, its patriarchal subliminal message is that even while a woman can be single, have a career, and live on her own, it takes a man to save her. Bridget’s ineptitude with cooking the meal and resulting panic trigger an emotional response with the reader of their own feelings of inadequacy and panic, culinary failures, and the conviviality of dinner with friends. However, the patriarchal undertone of the novel can be harmful as it perpetuates outdated gender norms, even given the humor of the novel and the cultural closeness we feel with Bridget’s ineptitude in the kitchen.

Food Writing and Memory

Food writing in literature can often be very evocative for the reader, triggering memories of childhood, past experiences, cultural identity, etc. Often, food writing in literature speaks to the reader of memory, whether it be personal, cultural, or just reading about the memory of a character in a novel. Marcel Proust, in his first volume of Remembrance of Things Past, Swann’s Way, has a four-page inner dialogue with himself on a memory that initiated with a madeleine and a cup of linden tea. In the book, Proust’s character is served the cake and tea and in his first drink, something evocative happens. His troubles are forgotten, he is filled with an undefinable joy, and he wonders what it is about that combination of the cake in tea that has triggered him to have these feelings. He experiments with the tea and eventually does remember. (Proust, 1982).

I raised to my lips a spoonful of the tea in which I had soaked a morsel of the cake. No sooner had the warm liquid mixed with the crumbs touched my palate than a shudder ran through me and I stopped, intent upon the extraordinary thing that was happening to me.

This passage in the novel is so iconic that the memory people often have triggered from a certain food is sometimes called a Proustian memory. It is this documentation of a mnemonic trigger that Tigner and Carruth call “gustatory spark” (Tigner & Carruth, Literature and Food Studies, 2018). However iconic, Proust is not the only author to trigger certain memories or visual food images that connect directly to the reader. It can happen with any book and any reader, a tug on the memory, a sense of familiarity, and the struggle to recall why this particular passage of a literary meal or food is so affecting. The reader will often search their memories until they find the corresponding visual image triggered by the gustatory spark. It may seem instantaneous but in reality, it is a mental categorization and retrieval filing system in the brain that ultimately delivers the flavor image or memory.

It is often assumed that it is Proust’s initial taste that caused instantaneous memory to occur. It did not. Instead, the smell of the combined cake and tea triggered certain reactions in Proust’s brain, acting as a mnemonic trigger, which he then delved into and explored out until the memory was clear. Still, readers continue to be fascinated with the Proustian description of a food memory because so often this mnemonic trigger via food and eating happens to us in our own brains. We recognize it, identify with it, and feel connected, and perhaps are a little entranced by it. This topic is so popular that scienfitic studies have been done to determine food’s effect on memory

In Neurogastronomy: How the Brain Creates Flavor and Why it Matters, author, Gordon Shepherd, explains the process by which the brain interprets food and creates a mnemonic trigger: “The narrator’s mouthful of crumb-laden tea thus activates a range of receptors tuned to the different volatile components, leading to impulse discharges that carry the information to the brain” (Shepherd, 2013, p. 176). Shepherd goes on to state:

It is this flavor image that was recognized by Proust’s brain, at first only indistinctly, as being part of a more complex memory that initially seemed beyond recall. The flavor image of the tea-soaked madeleine is thus metonymic for the complex multisensory image of the town of Combray.

Shepherd’s analysis of the neurological process identifying this complex memory disputes the idea of instant, involuntary recall and states that “our cognitive mechanisms have a gestalt quality in which we perceive and recall things as integrated wholes” (Shepherd, 2013, p. 180). While there are no actual smells of food experienced in literature that is infused with such writing, it appears that reading about food can create a type of visual food memory, rather than one based on taste or smell. The reader creates those flavor “images” based on their own memories, desires, and experiences, when they read about food. “Food memories are important not just because they concern sustenance but also because they have extensive connections to other memories of people, places, and things” (Allen, 2012, p. 152). The connections we make to food memories in literature, even without the sense of smell of a meal are important connections.

The reader connects with literary images of food, the characters that prepare it or eat it, and the language of food to their own memories of people, places, and things that are important to them. That is the allure of reading food writing in literature and why readers feel so connected to it. For the reader who has not had linden tea or madeleines, perhaps there will not be such a connection, but it can often generate a curiosity about that food and/or culture. Many readers have written about trying recipes or meals they read about to have that flavor experience or food experience/memory and not infrequently, those efforts have led to writing cookbooks.

Food Writing and the Literary Cookbook

There is a subsection of publishing that creates cookbooks based on literature, such as the Outlander Cookbook and other culinary offshoots of various novels and stories. In Literary Feasts: Inspired Eating from Classic Fiction, Sean Brand identifies various quotes from classic novels, and, for each one, gives a quick background on the meal, illustrations, what the reader will need to recreate it, and a rating system. The descriptions of what one will need to recreate a recipe from classic literature are often humorous and disappointingly, there are no real recipes in the book (Brand, 2006). Still, the vignette style of the book, combined with illustrations and quotations from each work cited, are enough to trigger a desire to read more, try to find the recipes, and attempt to re-create the meal. The memory of certain foods, found in literature or the memory of reading about such meals, helps us in our own definition of selfhood, another important function of food writing in literature.

In The Omniverous Mind: Our Evolving Relationship with Food, John Allen states: “Memory is essential to creating and maintaining the autobiographical narrative that defines the self” (Allen, 2012, p. 151). Selfhood or the definition of the self is something that is closely associated with food and eating, because the self is so closely attuned to culture and food is culture. Hence food memories, as they “can be classified as autobiographical memories concerning food” (Allen, 2012, p. 158) are deeply individual and personal. When we read about a literary meal that we feel connected to, we imbue it with that individual and personal connection, making it uniquely ours. That is another element that helps food writing in literature make such deep and abiding connections with the reader. Food writing connects us to ourselves.

Food Writing in Culinary Memoir/Gastrography

Culinary memoirs are immensely popular now and it is tempting to think that they are a relatively new phenomenon. However, at least ten books about cookery and dining are attributed to the first century Roman Marcus Apicius, so we know that a type of culinary memoir goes back at least that far. These books include helpful hints for the kitchen, such as how to test spoiled honey (Apicius, 1977)In their book, Reading Autobiography: A Guide for Interpreting Life Narratives, Sidonie Smith and Julia Watson discuss how the term “gastrography” “offers readers tasty pleasures and “food” for self-revision” (Smith & Waston, 2010, p. 148). The authors go on to posit that inclusion of recipes in such life narratives or culinary-based books act as a gift to the reader and that food can often “function as an evocation of the particularity of cultures and regions that life writers may imagine only in negative stereotypes” (Smith & Waston, 2010, p. 149). Conversely, Louise Vasvari argues that the term gastrography should not be used; she prefers the term “alimentary life writing” should be used (Vasvari, 2015). Vasvari also states that:

Recipe sharing, with its roots in oral storytelling is a vehicle for women to share stories and to reaffirm their identity within the community through recounting personal histories, to reminisce with others centered in food talk, to reiterate the importance of food as a storehouse of memories not dependent on happy childhood, but that recreates the fiction of one’s memories through food, etc.

Vasvari’s focus is on women’s recipes and stories but food stories, recipes, and foodways are not the exclusive territory of women. These writings transcend gender as well as genre and there is a seat for everyone at the food writing table.

Many gastrographies are written by men, such as the late Anthony Bourdain, who built a career in television based on his culinary memoir, Kitchen Confidential. However, culinary memoirs are written by both sexes. Bourdain’s book which led to a successful television career, was preceded by the success of Julia Child. Food critics such as Jeffrey Steingarten (The Man Who Ate Everything) and Ruth Reichl, (Garlic and Sapphires, Tender at the Bone, Save Me the Plums Remembrance of Things Paris, etc), have also written volumes on food, food writing, and foodways.

There are also biographies on such well-known chefs as James Beard, Jacques Pepin, and other chefs not all of whom have appeared on television. These chefs, can, as indicated in “Romanticised chefs and the psychopolitics of gastroporn [sic]” (Mentinis, 2017), act in a way that bestows social status as chefs, “as gatekeepers to high social status and symbolic ascension through provision of food and food commodities.” The celebrity chef imbues the consumer with the promise of selfhood and identity through their perceived expertise and the culinary metaphorics of the self. However, they also create their own identities through their mastery of cooking:

…to cook is thus to be able to reconfigure the self, to perform a transition from a certain type of selfhood to another by mastering the logic of the ‘forces’ that govern change. The kitchen is not simply the place where survival and pleasure are planned, but in actuality a place to contemplate the self…”

In reading about cooking in literature, readers too, can contemplate the self and learn about their own identities, form their identities, and empower themselves. Such is mentioned by Janet Wesselius, when speaking about children’s literary cookbooks, (Harde & Wesselius, 2020), argues:

…that food and eating are important in these narratives because they express the intellectual and social appetites and desires of Alice [Alice in Wonderland] and Anne [Anne of Green Gables] respectively and of their child readers just as they hunger for and consume food, so do they hunger for and consume social and intellectual nourishment.

This social and intellectual nourishment leads to creation of the self, building an identity, and self-empowerment, especially in the case of the young reader, which is why so much of children’s literature contains food writing. Reading about food in literature reminds the reader that they are not alone in the world. As David Goldstein asserts (Goldstein, 2017):

The second form of knowledge that eating can impart is the knowledge of the other self, or at least of the fact that there are other selves, ranged around us, eating or hoping to eat, full or starving. The second knowledge is the knowledge of the table and our relationships with those who sit around it or help make it possible.

Knowing that there are others who are hungry or eat differently but have the same human feelings and emotions helps a reader connect with those other selves and broaden their horizons: “Reading, like eating and food sharing, is also a kind of incomplete movement toward knowing” (Goldstein, 2017). Chefs contribute to this knowledge of selfhood, whether they be literary chefs, celebrity chefs, or even the amateur chef who prepares your meals.

The celebrity chef has a long history. From the gastronomic myth of Catherine de Medici bringing her own chef to France (Campanini, n.d.) to the fabled French chef, Francois Vatel, to Escoffier, and Bourdain, celebrity chefs have been visible and admired for their talent in creating delicious or innovative plates of food. Sometimes those dishes inspire literary writers and poets, not just the food critics. In more recent times with the advent of television, the internet, and social media, the celebrity chef has become romanticized and ubiquitous. Now, more than ever, these celebrity chefs are considered authorities and experts, often doling out advice on television, social media, in their memoirs, blogs, podcasts, and sometimes, even in novels written by or about chefs. The notion of chefs and cooks preparing wondrous, disastrous, or mundane meals finds its way into literature and food writing, which can also serve to help the reader find humanity in common with those that cook.

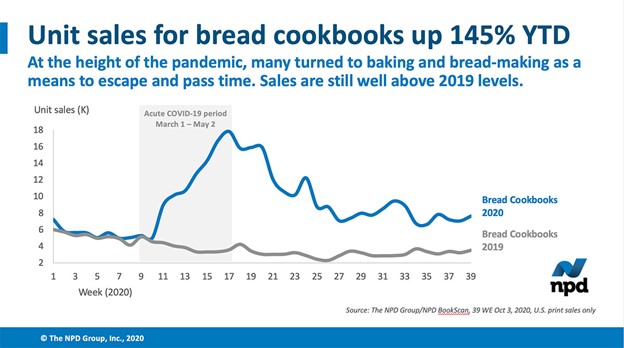

Reading about food and eating can help connect individuals and give recognition to another’s humanity. Culinary memoir and cookbooks offer a glimpse into the lives of those whose culture may be different, but who are committed to sharing their food experiences with others. At least in part, curiosity about unfamiliar food and food culture drives the sale of culinary memoir ad cookbooks. According to Lynn Z. Bloom, “Cookbooks alone weigh in at 12,400,00 hits on Google; Amazon.com lists 54,088 titles…There are (more or less) 151 million food blogs…” (Bloom, 2008). This 2008 data gives a basic idea of just how far-reaching food writing is. The global pandemic of 2020 increased those numbers. According to the New York Times, which claims the pandemic has been a boon to the cookbook industry, “overall sales jumped 17 percent from 2019, according to figures from NPD BookScan, which tracks about 85 percent of book sales in America” (Severson, 2021). The article also states that the type of cookbooks written and sold, and the food stories shared, are becoming part of our pandemic history and “cultural artifacts of the year when a virus forced an entire nation into the kitchen.” If food in literature is used to communicate the everyday, then food writers become historians of a sort, documenting history, and culture through foodways.

In fact, cookbooks relating to bread-making rose 145% in 2020 due to the pandemic (Table 1). If our cookbooks in a pandemic year stand up to history as cultural artifacts of a deadly pandemic and what we, as humans, did to survive it and find a way to be connected through food, then the literature of food is clearly vital. This is not the first time humans have used food writing and foodways to survive pandemics or other trauma.

Giovanni Boccaccio, between the years 1349 and 1353, wrote The Decameron, a collection of allegorical stories. The book, written just after an actual pandemic in Florence, the Black Death, tells of a group of young people who elude the plague by escaping to the Tuscan countryside and turn to storytelling to keep their spirits up. all the wonderful meals the young people had, we know they feasted on “dishes exquisitely concocted…and delicate wines” (Boccacio, 1955, p. xxxii). What were these dishes and wines?

The identity of Boccacio’s exquisite dishes is the subject of great speculation by historians, food writers, and readers alike. In The Paris Review, a literary periodical, columnist, Valerie Stivers, writes a column entitled “Eat Your Words” wherein she creates menus from literature and cooks the recipes. In her column, she has cooked using inspiration from a variety of literary works, including Boccaccio, “My hands smell like strawberries and chicken liver, and I’m drinking a Vernaccia, the “good white wine” of The Decameron” she writes in one pandemic column (Stivers, 2020). As she cooks, she scrolls her phone for death tolls from the pandemic and writes about the modern-day plague’s effect on her.

Like many in the early days of the pandemic, Stivers turned to reading Boccaccio, and taking a further step, cooked up a literary menu that could have been eaten by those ten young people from his pages. She attributes a five-course, all-chicken meal to “pandemic thrift” a dirty joke in the book in The Decameron. The meal includes, chicken candy and strozapretti (priest stranglers). All of Stivers’ “Eat Your Words” columns are delightful forays into the food of literature but this one, because of the lack of specificity in Boccaccio’s work and the mindset of the pandemic, feels particularly close to home. Unlike Boccaccio’s characters, we do not all have a Tuscan hideaway complete with a wonderful Italian chef to create exquisite dishes, so we wonder what they ate and still feel a sense of connection to them across centuries and oceans.

A recently published scholarly text entitled, Consumption and the Literary Cookbook (Harde & Wesselius, 2020), offers the first book-length study of literary cookbooks. In that collection of essays, the editors discuss a diverse corpus of narrative cookbooks. In New Books in Food, an Audible podcast, authors Harde ad Wesselius talk about trust within the literary cookbooks, citing how problematic authors and chefs can break that trust within literary cookbooks, citing how problematic authors and chefs can break that trust with the reader. In particular, they discuss Mario Batali, calling him a “Me Too” chef because of his alleged sexual harassment of women. The authors had previously loved his cookbooks and found them to be reliable but now will not read them because of the breach of trust.

Food Writing, the Literary Table, and Culture

Food writing in literature matters because it calls to mind our own cultural memories of the table, the conviviality of its guests and family, or conversely those famous holiday meal family fights. The table, and meals it facilitates, loom large in many novels, children’s literature, nonfiction, and even the ancient classics, such as the Bible or the Platonic Symposium. In the Bible, there is also focus on the literary table/meal. For example, Jesus performs one of his miracles at a wedding feast in Cana, during which he transforms water to replace the wine that had run out (Carroll, 1997, 4 John 46). In another instance, Jesus ensures that a small quantity of bread and fish abundantly feed the thousands who have come to hear him preach (Carroll, 1997. 14 Matthew 17-21). Finally, during the Last Supper, wherein Jesus reveals to his friends that one of them will betray him, Jesus makes a show of breaking unleavened bread and drinking wine, (Carroll, 1997, 26 Matthew 26-29) in celebration of Passover, he declares that the food has become his body and blood, and exhorts his friends to repeat the ceremony in the future as a way of preserving his memory. The lyrical Song of Solomon offers many examples of food writing, such as “Stay me with flagons, comfort me with apples: for I am sick of love” (Carroll, 1997, 2 Solomon 5). The Song mentions figs, wine, feeding, saffron, cinnamon, honey, milk, pomegranates, etc. It is filled with symbolism, allusion, metaphor, and food writing.

Novels offer an abundance of examples of the literary table, In The Age of Innocence, Edith Wharton displays not only the socio-economic status of her characters, Archer and May, but also details the enormous constraints their privilege (and May) impose on Archer. The elegant and very detailed setting illustrates the regimented order of their status and wealth as well as how much appearance matters in their world. Types of food, dishes, glassware, silverware, and even placement strategically flaunt the Archer’s wealth and position in a type of semiotics of wealth and privilege that every character understands. However, what is underneath all this ostentation is the fact that it is so regimented, nothing can be overlooked, and that while their wealth affords them much luxury and comfort, they are also trapped in a narrow and highly restrictive environment, from which they do not dare deviate

The elegance and obvious expense of the meal does not show the work it took to create it, nor what it has cost the servants in time and effort, or what those same servants have for their own meals. The meal serves to showcase May and prove to her peers that she is worthy of their respect, that she has wealth and knows how to use it, but it does not attribute any of that effort to the people that worked so hard to prepare it and make it memorable (Wharton, 2012, p. 750):

“But a big dinner, with a hired chef, and two borrowed footmen, with Roman punch, roses from Hendersons, and menus on gilt-edge cards…the Roman punch made all the difference; not in itself but by its manifold implications-since it signified either canvas-backs or terrapin, two soups, a hot and a cold sweet, full dècolletage [sic] with short sleeves, and guests of proportionate importance.”

What the meal also serves to do is to make Archer feel intensely uncomfortable and desperate to escape his marriage and start a new life with Ellen Olenska; at the same time, he realizes his peers know of their affair and think less of him. It serves to illustrate the emotional torment he experiences and how conflicted he feels by his duty/position and the need for personal fulfillment. Further, the meal, as planned by his wife May, serves to firmly trap Archer in their marriage, when May informs Archer she is pregnant.

According to Massimo Montanari, food, and everything about it, is culture. In his book Food is Culture, he discusses written cuisine as it “permits the codification, in an established and recognized medium, of the practice and techniques developed by a specific society” (Montanari, Food is Culture, 2006, p. 35). Further, he states:

Food is culture when it is produced, even “performed,” because man does not use only what is found in nature…but seeks also to create his own food, a food specific unto himself, superimposing the action of production on that of predator or hunter. Food becomes culture when it is prepared …Food is culture when it is eaten.

If food is culture when it is produced, prepared, and eaten, as Montanari claims above (Montanari, Food is Culture, 2006), then food, when it is written about, is culture as well.

In writing about food, whether in fiction, non-fiction, or any other genre, an author establishes setting, a meaning, signpost, or a historical reference to help the reader understand what is going on in the work or and to become more engaged in it. The writer creates connections by expounding on something ubiquitous in every culture and familiar to every individual – food and eating. We see many of these types of connections in literature.

For example, in Oliver Twist, the reader instantly connects with Oliver in Chapter II, (Dickens, Oliver Twist, 1993, p. 27) because all humans can relate to the idea, if not the reality of hunger, and the image of a hungry child pulls at some emotional connection:

Child as he was, he was desperate with hunger, and reckless with misery. He rose from the table; and advancing to the master, basin and spoon in his hand, said: somewhat alarmed at his own temerity: “Please, sir, I want some more.”

Dickens knew what he was doing in writing these lines and his fulsome descriptions of how hungry Oliver was, what he was fed (gruel) were intended to highlight injustice and provoke compassion among his audience. Readers sympathize and empathize with Oliver while hating the master who hit him on the head with a ladle just for asking for more. Dickens often used hunger to illustrate poverty and social issues in his work as a way to encourage reform (Editor, 2018). Dickens himself had often been hungry and heused that life experience to create social change by getting the reader to experience that sense of hunger for themselves.

In A Tale of Two Cities, Dickens expounds on hunger using the literary device of repetition. By repeating the word, “hunger,” Dickens ensures that reader is immersed in the poverty of the people who experience it. He creates setting, character, and a rallying cry against poverty and want in this rather long quote, which uses the device of repetition to great effect (Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities, Bantam, p. 30):

The mill which had worked them down, was the mill that grinds young people old; the children had ancient faces and grave voices; and upon them, and upon the grown faces, and ploughed into every furrow of age and coming up afresh, was the sigh, Hunger. It was prevalent everywhere. Hunger was pushed out of the tall houses, in the wretched clothing that hung upon poles and lines; Hunger was patched into them with straw and rag and wood and paper; Hunger was repeated in every fragment of the small modicum of firewood that the man sawed off; Hunger stared down from the smokeless chimneys, and started up from the filthy street that had no offal, among its refuse, of anything to eat. Hunger was the inscription on the baker’s shelves, written in every small loaf of his scanty stock of bad bread; at the sausage-shop, in every dead-dog preparation that was offered for sale. Hunger rattled its dry bones among the roasting chestnuts in the turned cylinder; Hunger was shred into atomics in every farthing porringer of husky chips of potato, fried with some reluctant drops of oil.

Dickens uses this quote about food, and its lack, to showcase widespread hunger. From the first to the last word, he uses hunger to drill in the image of starvation and poverty. In the last sentence, his food writing illustrates the absolute paucity of food with his imagery of “chips of potato, fried with some reluctant drops of oil.” The word “reluctant” is a particularly good choice as the reader can imagine remnants of oil in a bottle, enough to seem like there is some in there and yet, not enough will come out to fill the pan. That reluctance is not only an indicator of poverty, it is an indication of class as well. Those higher up on the social and financial ladder would have sufficient funds to purchase groceries and hire someone to cook the food. Unlike the people in this quote, the wealthy would not worry anxiously about whether the last drips of oil would be enough to fry their food.

In yet another Dickens novel, Great Expectations, one o of his characters is often hungry, while in A Christmas Carol, much attention is paid to the goose and plum pudding. With delicious examples of food and its preparation, (such as the flaming pudding), one may think Dickens was obsessed with food and perhaps he was. In his day, Victorian England had a national fear of famine, brought on by the Corn Laws, the Poor Laws, arrival of Irish immigrants from the potato famine, etc. As Tara Moore explains, “Authors writing during the early years of Victoria’s reign have left memorable images of starvation to commemorate what they saw as societal and political failures.” (Moore, 2008). Moore goes on to discuss how starvation was in the news constantly; it became part of a national consciousness. The literary Christmas meal described by many Victorian authors seems a response to that fear. Dickens also wrote about classism in his novels, used hunger and food help to illustrate divisions of the social classes, and injustices towards the poor.

More than a century and a half after Dickens wrote, and particularly as the worldwide pandemic continues, we see hunger in our own society, as well as homelessness, and disease. “Food insecurity” is the watchword these days rather than the more stark “hunger” or “starvation.” However, those visceral conditions of want and poverty are still prevalent and today’s writers will reflect on that, much as Dickens and other Victorian writers did. Just as the authors during famine wrote about the famine-induced Irish Diaspora, modern-day writers are already documenting their own tales of diaspora, displacement, and trauma through food writing.

Iranian author, Afsaneh Hojabri, writes about Iranian women and their food narratives of diaspora as a means of keeping their culture alive, connecting them to their homeland, giving them a sense of belonging in their new homes, and writing as a means to educate the public about their culture and what they lost through their diaspora. Hojabri states writing about food is also a way of “providing a cultural guide highlighting Iranian rich history, its cultural, linguistic, climatic, and culinary diversity, and emphasizing its pre-Islamic traditions, thereby distancing themselves from the Islamic state” (Hojabri, 2020). For these Iranian writers, food writing is a way to heal, to bridge their old world to their new one, and to find commonality amongst others. Their writing also serves to showcase their cultural pride and generosity. By sharing their food narratives and recipes, Iranian women writers are bringing their traditions and foodways to the literary and global tables.

They are not alone in sharing their culinary culture. There seems to be amongst food writers, a generosity of spirit that says, “Welcome to our table.” Laura Esquivel, in her novel Like Water for Chocolate tells the tale of long-suffering Tita, a younger sister in a very traditional Mexican household, whose only comfort is in the kitchen. Esquivel blends magical realism, recipes, and star-crossed lovers to tell her tale, thus sharing some very traditional Mexican recipes, along with her story (Esquivel, 1989). While the reader is caught up in the plot, they cannot help but bookmark the recipes to re-create later in their own kitchens.

Esquivel is not unique in making the kitchen central to her narrative. Janice Jaffe writes of Latinx authors like Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, Puerto Rican author, Rosario Ferre, Helena Viramontes, and others who “reclaim the kitchen as a space of creative power” (Jaffe, 1993). The creative space and power of the kitchen is also integral to food writing, which in turn, is integral to writing about nearly everything.

The kitchen, like food, is vital because it is where we go to create anything from the simplest cup of tea to an elaborate five-course meal. The kitchen’s power is in the limitless possibilities, which, like food writing, cross over into nearly everything we do. Sometimes, the kitchen table is for writing, office work, drawing, homework, cooking, and eating. Food writing brings those possibilities to literature. The biggest part of the kitchen’s allure, though, is that it is where food is kept, prepared, and often eaten. Because food is so vital to humans, the kitchen stands as the symbol of food, comfort, safety, family, etc. and that is why the descriptions of kitchens is also an important addition to food writing in literature. “The kitchen is not simply the place where survival and pleasure are planned, but in actuality a place to contemplate the self” (Montanari, Let the Meatballs Rest and Other Stories About Food and Culture, 2012). Further, as Welleck and Austin state in their book, Theories of Literature, “domestic interiors may be metonymic or metaphoric expressions of character” (Welleck & Warren, 1984) Those interiors represent maternalism, safety, and warmth. It is therefore a safe place to contemplate the self.

If the kitchen is the place where we contemplate the self, it would stand to reason that cooking, an act of creation, is the how we help to construct the self.

Reading about kitchens, cooking, and food, helps not only to connect with the self but to aid in constructing it. It is unsurprising, therefore, that food writing is omnipresent in children’s literature. As stated by Keeling and Pollard in Critical Approaches to Food in Children’s Literature, “Food experiences form part of the daily texture of every child’s life from birth onwards, as any adult who cares for children is highly aware; thus it is hardly surprising that food is a constantly recurring motif in literature written for children” (Keeling & Scott, 2009). Children are always tasting things in children’s literature. For example, after falling down the rabbit hole into Wonderland, Alice tastes the “Drink Me” bottle and compares the flavor to a variety of the exotic and the ordinary. As stated in Tablelands: Food in Children’s Literature, Alice’s experience relates to Brillat-Savarin’s “I feel, having set forth the principles of my theory, that it is certain that taste causes sensations of three different kinds: direct, complete, and relective” (Keeling & Pollard, 2020). Roald Dahl’s children’s books also spend a lot of time discussing taste and food. In Laura Ingalls Wilder’s books, food, both the production, hunting, growing, cooking, and eating is a constant. The food writing in those books, inspired cookbooks, blogs, and recipe recreations. In Brian Jacques’ Redwall, , anthropomorphic characters (mice, voles, rats, badgers, etc.), are monks, who live in an abbey and are always eating (when they are not warring); like the Little House books, there is frequent focus on the production and preparation of food (Jacques, 1986).

Brother Alf remarked that Friar Hugo had excelled himself, as course after course was brought to the table. Tender freshwater shrimp garnished with cream and rose leaves, devilled barley pears in acorn pureé, apple and carrot chews, marinated cabbage stalks steeped in creamed white turnip with nutmeg.

Like Alice in Wonderland, the Little House books, and Redwall, there exists the three points of Brillat-Savarin: direct, complete, and relective. As stated in the Irish Times, “food is often representative of limitations imposed on upon a child’s world, blending well with the idea of excess as a key element of childhood fantasy” (Flanagan, 2017). The article also refers to Bruno Bettelheim’s The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales and how Bettelheim considers the use of food in this type of literature.

Fairytales often contain food writing. In “Hansel and Gretel,” for example, the titular characters find a house in the woods built of sweets. It is bait, intended to lure children in so the witch who lives there can eat them. Instead, they turn the tale round on the witch and shove her into an oven (Grimm & Grimm, 2012). In “Cap O’ Rushes,” an English fairytale, the youngest daughter tells her father she loves him “more than fresh meat loves salt.” He believes she does not love him since salt is seemingly mundane and ordinary so he casts her out of the castle. Eventually, Cap o’Rushes gets a job as a servant in another castle and marries the prince. She invites all the neighboring nobles and in particular, her father. She orders all the meat to be served without salt and when her father tastes it, he realizes what his daughter was trying to tell him about her love for him (A Dictionary of English Folklore, 2003). Fairytales often use didactic methods of food writing in order to convey a moral message. Scholars are still uncertain why so many fairy tales, like that of Hansel and Gretel or Little Red Riding Hood rely on cannibalism to deliver that message. Are they appealing to children’s deepest fears or do they hearken back to ancient times when obtaining food was a desperate struggle? Regardless, food is central in many fairy tales, whether there be cannibalistic references or not.

Even the seemingly simple act of writing a menu can be literature and sometimes, it is almost poetic. How a menu is written and what it includes, can give its reader indications of class, cost, and more. In The Language of Food: A Linguist Reads the Menu, Dan Jurafsky states that attention to detail, origins of the ingredients, and marketing techniques are designed to entice the reader to pay for expensive items (Jurafsky, 2014, p. 9). Jurafsky explains how certain words have subtle meanings and metaphors. While Jurafsky’s focus is on menus, his insights also hold true for the meanings and metaphors that about in literary food writing and can help decipher hidden meanings in other types of literary texts.

Food Writing and What It Hides

Obfuscation of problematic issues can be found in Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden, a beloved children’s book whose protagonist, Mary Lennox, an ill-tempered, skinny, unhealthy, and rather ugly orphan whose parents have died of cholera in India. The book details the time in India when her parents died, the resulting search for family in England, travel to said wild place on the moors in Yorkshire, a rather Gothic setting, and her life there with a mostly absent hunchbacked uncle and the servants (Burnett, 1987). The book details the time in India when her parents died, the resulting search for family in England, travel to rural Yorkshire in England, and Mary’s life there on the moors with a mostly absent, hunchbacked uncle and his servants (Burnett, 1987). The book is best remembered for the secret, walled garden that Mary discovers at her uncle’s home; but many readers ignore Burnett’s disparaging descriptions of the food Mary ate in India, as well as the Indian climate and people (Burnett, 1987).

There is no doubt that the fresh, strong, pure air from the moor had a great deal to do with it [fueling her imagination]. Just as it had given her an appetite, and fighting with the wind had stirred her blood, so the same things stirred her mind. In India, she had always been too hot and languid and weak to care much about anything, but in this place, she was beginning to care and to want to do new things. Already she felt less ‘contrary,’ though she did not know why.

Through her negative descriptions of the region and how its weather promoted Mary’s listlessness, lack of appetite, sallow complexion, and thinness, Burnett manages to express disdain for India and espouses a strongly English, nationalistic, and racist perspective. In other passages, it is implied that good English food, such as porridge, tea, and toast, along with the now-present appetite because of the English weather, are responsible for Mary’s transformation from ugly orphan to a happy little girl. Despite these problematic elements, The Secret Garden remains a popular children’s book and has inspired numerous theatrical and film adaptations. It also stands as a historical glimpse into how racism, bigotry, and Othering were viewed as normal and perfectly acceptable in the not-so-distant past.

Food Writing and the Accidental Historian

In Miguel De Cervantes de Saavedra’s Don Quixote, much attention is paid to food. Cervantes writes food descriptions through the eyes of his character, Sancho Panza. In the episode of the wedding of Camacho, a rich farmer, Sancho awakens to the smell of food cooking, “there’s a beautiful smell coming that’s got more to do with fried rashers than with galingale and thyme – by all that’s holy, a wedding that starts with smells like this is bound to be a plentiful and lavish one!” ( (Cervantes, 2018, p. 616). The protagonist, Don Quixote scolds his servant, Sancho Panza for being a glutton and Sancho goes off to saddle the horses. When they arrive at the wedding, the first thing Sancho sees is a whole ox spitted over an elm trunk and the passage goes on to describe cooking pots, spices, pigs, honey, how the food was being cooked, etc. The preparations indicate that the cook at the wedding was making a stew known as olla podrida, a national dish of Spain, though it does not state such in this translation. In a journal article, entitled “Spanish Culinary History in Cervantes’ “Bodas de Camacho” (Nadeau, 2005), Carolyn A. Nadeau argues that the olla podrida in the wedding of Camacho illustrates how Cervantes honored “Spain’s past traditions and celebrates nuances of an emerging modern culinary art form.” She also states that during the sixteenth century, when Cervantes published his novel, Spain and other European countries were undergoing “a gastronomic revolution with dramatic changes in foodstuffs and methods of preparation” (Nadeau, 2005, p. 348). Nadeau argues that Cervantes’ literary banquet reflects the “gastronomic changes that were occurring in early modern Spain” (Nadeau, 2005, p. 350). Further, the olla podrida, or the stew that Sancho Panza observes the cook making at the wedding, was an a la mode dish during the Hapsburg monarchy but that everyone from nobles to peasants enjoyed what was often referred to as “la princesa de los guizados” or the princess of stews. “For three centuries, is served from the richest tables to the poorest.” (Nadeau, 2005, p. 350). The stew’s recipe often varies but it is considered to be one of Spain’s national dishes. While Cervantes was not the first to catalog this dish, that honor being Diego Granado’s Libro del arete de cozina [sic], Don Quixote documents a moment of gastronomic change in Spain’s history for posterity. Thus Cervantes, in writing a comedy, also becomes a documentarian and culinary historian for his era. Therefore, Cervantes, unwittingly, became a voice for the gastronomic traditions of Spain. In Don Quixote, he celebrated not only the food, but the preparers of it, and gives the reader an idea of the food philosophy the people of Cervantes’ era had, while also documenting the emergence of a national dish.

Food Writing and Philosophy